"We're in a giant car heading towards a brick wall and everyone's arguing over where they're going to sit."

Why do we argue? How can an opinion be right or wrong? Is a correct opinion just a fact? How can multiple smart, well-edjucated, like-minded people find different conclusions to the same question?

People argue for many reasons, to establish dominance and control, to defend their beliefs, to express emotions, to gain information, or to resolve conflicts. I argue because I’m right and people need to know it. I have a group of friends. That’s the truth. No arguing it. That group of friends argues a lot. We argue passionately. We argue over dumb stuff. This week was no exception. Here was the fundamental question we debated: “”How many average human males would it take to defeat a wild horse in a deathmatch in an enclosed area if they are bare handed without tools?” For the sake of the logical journey on which we are about to embark, I am redefining the question as, “How many average human males would it take to capture and take down a wild horse in an enclosed area if they are bare handed without tools?” to avoid the idea of killing a horse.

How do you even begin to approach a hypothetical like this? We must approach this question by asking a series of more fundamental questions. How do we quantify this issue? Is there a base level of success? One person might accomplish the task 1% of the time, but that hardly feels like an acceptable answer. Does it need to be a 51% success rate to be acceptable? Is this simply a matter of opinion? If so, can an opinion be correct or incorrect? By definition, an opinion can be neither correct nor incorrect, as opinions are subjective and personal beliefs or judgments about something that are not based on evidence or proof. However, it’s important to note that while an opinion itself may not be correct or incorrect, the arguments or reasoning used to support an opinion may be based on misinformation or faulty logic, making the argument itself flawed. This then leads us to a concept we may mistake for opinion. A moral fact. The concept of moral facts is a complex and controversial topic in philosophy. Some people believe that moral facts exist, while others argue that morality is entirely relative and subjective. This is steering us away from the topic at hand though and it is already going to be a long pondering. That said, here are some other fun questions to ponder in your free time. “Can you make a correct decision that yields the incorrect result?” and “Can anything ever be “absolute”?” Been thinking about that this week.

Back to the argument at hand. For our group of friends, we need a winner and a loser. So now we must ask, If 2 sides are debating a hypothetical scenario that will never be realized, can one of them be right and one wrong? I believe the answer is yes. It’s possible for two people to have opposing views on a hypothetical scenario that will never be realized, and for one of them to be right and the other wrong. This is because the accuracy of an argument depends on the reasoning and evidence used, rather than the outcome of the scenario. That said, I am coming at this topic from a biased perspective as I strongly argued one side of the debate. So, we are going to take a walk through history and see how the concepts of logic and argument developed looking through the lens of our specific question.

Where did the study of logic begin?

5th century BCE: Greek philosopher Zeno of Elea develops the concept of the paradox, which challenges traditional notions of logic and truth. If he were to approach the question “How many average human males would it take to capture and take down a wild horse in an enclosed area if they are bare handed without tools?”, he would likely use his paradoxical approach to challenge common assumptions and arrive at a unique conclusion.

Identifying the paradox:

Zeno may start by identifying any paradoxical elements in the scenario, such as the disparity in strength and agility between the average human males and the wild horse.

Resolving the paradox:

Zeno may then use his philosophical method of reducing the paradox to a series of smaller paradoxes, each of which can be resolved such as:

What is the definition of average human male strength and agility?

What is the definition of wild horse strength and agility?

How can we accurately measure the disparity between the two?

What does it mean for one to be stronger or more agile than the other?

Can we compare human and horse abilities in a meaningful way?

We are making a large question easier.

4th century BCE: Greek philosopher Aristotle formalizes the study of logic, introducing the syllogism as a method of deductive reasoning. He also develops the concept of the syllogism and the laws of thought, including the law of non-contradiction and the law of the excluded middle.

-

- Identifying the premises:

a. Aristotle would start by identifying the premises or facts of the scenario, such as the physical characteristics and abilities of average human males and wild horses.

-

- Formulating the syllogism:

a. Aristotle would then use these premises to form a syllogism, or an argument, using the laws of thought, including the law of non-contradiction and the law of the excluded middle.

An example might be:

Syllogism:

If an average human male has limited physical strength and abilities, then capturing and taking down a wild horse bare handed without tools would be challenging for one individual.

If capturing and taking down a wild horse bare handed without tools would be challenging for one individual, then it would likely take more than one average human male to accomplish this task.

Conclusion: It would likely take more than one average human male to capture and take down a wild horse in an enclosed area if they are bare handed without tools.

Now we’re getting somewhere!

-

- Applying the laws of thought:

The law of non-contradiction states that something cannot both be and not be at the same time and in the same respect. In this syllogism, both premises, “An average human male has limited physical strength and abilities” and “A wild horse is significantly stronger and more agile than an average human male” cannot both be true and false at the same time and in the same respect.

The law of the excluded middle states that either a proposition is true or its negation is true. In this syllogism, it is either the case that an average human male has limited physical strength and abilities or it is not the case. If the first premise is true, then the conclusion must also be true.

Based on the laws of thought, this syllogism is valid and the conclusion follows logically from the premises. The conclusion, “It would likely take more than one average human male to capture and take down a wild horse in an enclosed area if they are bare handed without tools,” follows logically from the premises and is therefore considered to be logically deduced.

11th century CE: Arab philosopher and logician Al-Farabi writes the “Book of Opinion,” which lays the foundation for modal logic, which is concerned with the logical relations between statements and the way they are necessary or possible.

This was mainly a compilation of the previously stated ideas.

Clearly our take away truth to tuck away is a horse is much more powerful than an average human male (The Rock is an exception) thus it would take multiple men to take down a horse.

We will now skip ahead as most logic and reasoning became mathematical for a while. I’ve tried running a few mathematical simulations using these systems to find a definitive number of humans but the amount of variables and lack of any previous testing makes this impossible.

20th century CE: Mathematical logic and set theory are developed into a formal system by logicians such as Bertrand Russell, Alfred North Whitehead, Kurt Gödel, and others. This is the most thorough model and borrows from mathematical logic.

Identifying the premises:

a. Premise 1: A wild horse is a strong and powerful animal.

b. Premise 2: Average human males are physically limited in strength and agility compared to a wild horse but have the advantage of intellect and creativity.

c. Premise 3: The scenario involves capturing and taking down a wild horse in an enclosed area with bare hands without tools.

Formalizing the argument:

a. Let H = {h1, h2, …, hn} represent the set of n average human males involved in the scenario.

b. Let W = {w1} represent the set of the wild horse in the scenario.

c. The objective is to capture and take down w1 with the elements of H using their intellect and creativity.

Evaluating the consistency and completeness:

a. Determine the physical capabilities and limitations, as well as the intellect and creativity, of the elements of H and W.

b. Consider all possible scenarios where n elements of H work together to capture and take down w1 using their intellect and creativity.

c. Evaluate the consistency and completeness of each scenario in terms of the physical capabilities and limitations of H, the intellect and creativity of H, and the strength and agility of W.

Evaluating the validity:

a. Evaluate the validity of each scenario based on the physical capabilities and limitations of H, the intellect and creativity of H, and the strength and agility of W.

b. Determine the scenario that results in the most valid and feasible solution for capturing and taking down w1 with H using their intellect and creativity.

Refuting counter-arguments:

a. Consider alternative scenarios where n elements of H work together to capture and take down w1 in different ways, utilizing different combinations of their physical capabilities, intellect, and creativity.

b. Evaluate the consistency, completeness, and validity of each alternative scenario.

c. Refute counter-arguments based on the results of the evaluation of alternative scenarios.

Drawing conclusions:

a. Based on the results of the analysis, draw conclusions about the number of average human males needed to capture and take down a wild horse in an enclosed area with bare hands without tools, utilizing their intellect and creativity.

b. Provide evidence to support the conclusions and explain why they are the most well-supported based on the available evidence.

We still don’t have a definitive answer, but we have a clear road map to get there.

Why did I waste your time with the history of logical thought? Because that is how I argue everything in my life. I play to win. If I am debating something high stakes or something sports related. Last week we discussed pressing in and asking “why?” The more I write, the more I realize how much I crave digging deeper and learning. Maybe I need to learn to let things go. In the heat of the horse debate, I was singularly focused. Tunnel vision pointed at winning. That said, if I was the kind of person who could let things go or who could ever satisfy my thirst for knowledge, you wouldn’t be reading this newsletter.

Hand Selected Articles From Me To You

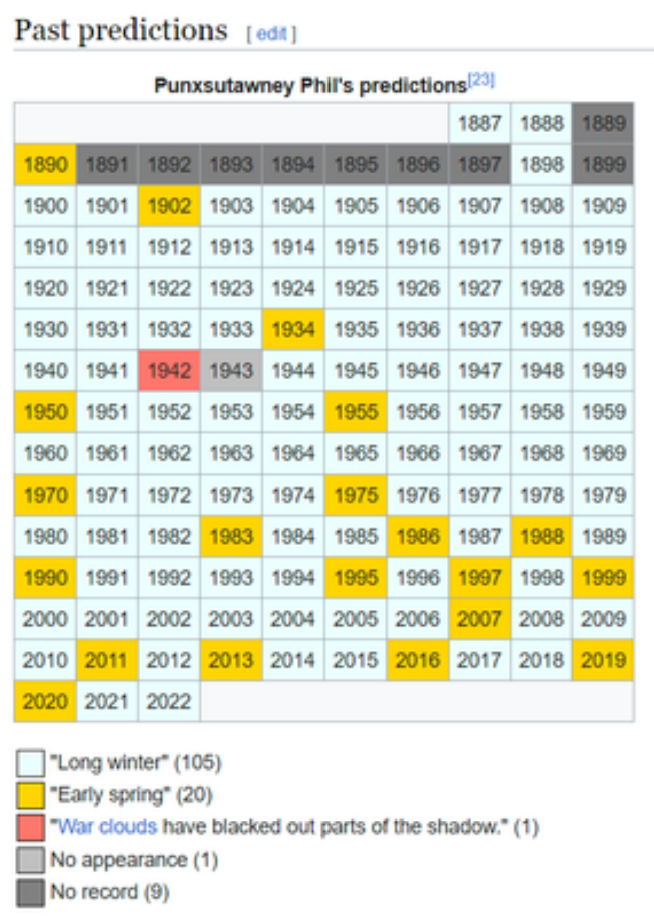

This week, I am presenting a few funny sections from Wikipedia articles and links to additionally interesting articles. There is a world of wikifun to be had.

New format, same self gratifying, vociferous, “Look at me I’m smart” Seth. What a tool. I’m the new intern in charge of writing the outros (and getting coffee that is “Goldilocks style” because apparently saying, “just right,” or, “the way I like it,” is too pedestrian for Seth.) Asshole. He doesn’t proof read these so we should be fine. Have a good day everyone. It’s the freakin’ weekend after-all. Also, Happy Birthday Will, you really earned it this year. Go Birds, the refs saved the Chiefs in

Burrowhead, and Andy Reid still loves Philly more.

All My Love,

Seth Winton